by Nancy Christofferson

HUERFANO — It’s probably just a coincidence, but ever since I celebrated my half birthday a couple weeks ago, I can’t stop thinking about dinosaurs.

Most of us in our little chunk of the globe know full well that once upon a time, millions of years ago, our now semi-arid environment was lush, swampy and often under water (otherwise, how does one explain all those coal deposits?).

Something I read recently informed me the soil in my garden is two million years old (and here I thought it had just come in yesterday from Alamosa!) This reminds me that we are literally walking on history.

Who first noticed the huge fossilized bones, the imprints of ferns and sea creatures embedded in stone? Because ancient Native American rock art and campsites have been found in close proximity to some of these fossil features, we know they were aware of their existence, but not their age or appearance when alive. It was no doubt some of these gigantic bones that became incorporated into their creation stories.

In later times, when geologists and paleontologists pieced together the remains of the flora and fauna of earlier ages, they continued to search out these fossils and today we have a fairly good picture of what was here. Or, at least, a picture devised from science tempered by a bit of guesswork based on physical evidence. Luckily, we also had newspapers to chronicle some of their findings.

No doubt some of the first Europeans of the 15th and 16th centuries saw some of the same bones and fossils that had inspired the Native Americans many centuries before when they first penetrated the Great Plains of eastern Colorado. These explorers were mainly searching for familiar species of flora and fauna that were of value to their way of life by being medicinal or edible.

The early American expeditions noted the natural attributes of the prairies and mountains in the 1800s, recording them with sketches and assigning scientific names to them. One of these was F.V. Hayden, whose knowledge showed him the various plugs and dikes that dotted southeastern Colorado in 1869.

All of them must have been puzzled by the bone deposits they ran across, though they were quick enough to realize the value of coal seams and other minerals. However, pure science was still far from explaining other features.

One of the first species in our area to be identified by scientists was evidently the eohippus, or dawn horse. Fossils of this tiny ancestor of the horse were first found in Mongolia and dated to around 55 to 45 million years old. The creature had stood about eight to 14 inches high, weighed maybe 35 pounds and appeared in the Tertiary period. Its descendants also included hippos and tapirs. These same fossils were found in Cucharas Canyon.

Incoming experts

Experts from the American Museum of Natural History first visited Huerfano County in 1896, when they headquartered at Farisita and worked west, “continuing down to the divide between the Huerfano River and Muddy Creek and two miles north and south”. They found enough of interest to cause them to return in 1916-18.

Perhaps local residents were surprised to find bones, but no one gasped when Young Farr in 1904, following several rainstorms, “found the skull of some prehistoric monster” along Bear Creek.

In 1907 geologists from Colorado State University went exploring and found the remains of a large mastodon in the bottom of Jack Arrington’s reservoir five miles north of La Veta. Mastodons are many millions of years younger than eohippus, but thousands of years older than us. They weren’t dinosaurs, but they ARE fossilized.

Their search must have been widespread, because the students of the geology classes at Huerfano County High School in Walsenburg went to the “fossil beds south of town and obtained nice specimens” in l908. The following year, Mrs. E.A. Lidle, whose ranch was just southeast of Walsenburg, sent the university a fossil skull of “a gigantic ground sloth”. This may have been the prehistoric monster found a few years earlier or another species altogether found in the same proximity.

Worth a look

Geologists, not paleontologists, became regular visitors to Huerfano County around 1900 when oil and gas exploration proved the existence of both. In 1928 they found a dinosaur tooth and other remains near the Alamo oil well.

Imagine the surprise, in 1932, when “Thomas Anselmo, while working on his ranch on Bear Creek, unearthed mammoth bones including a 12-inch long molar”. It was put on display in the Fox-Valencia Theater in Walsenburg.

Speaking of “on display”, La Veta’s well known builders, the Coleman brothers, were excavating for stone for school construction on Pinon Hill north of town when they ran across numerous odd triangular shaped rocks. They discovered them to be sharks’ teeth, and they could be seen in the window of the drugstore.

One day in 1933, “Fred Bergamo and Arthur Ryan, both of Walsenburg, found a petrified egg near an abandoned cabin between Cuchara Camps and Stonewall”. This was determined to be a fossilized dino egg of some unknown species, but it made its way to the window of the World-Independence office, if not beyond.

The W-I itself stated in October 1936, “Proof that Walsenburg citizens are living on a sea bottom was substantiated by officials who identified fossils found in city limits as 60 million years old sea creatures”. The fossils were found to be a creature similar to a nautilus, which was related to an ammonite, a circular sea bottom resident whose shell was snail-like. The nautilus grew in a straight line, but is no less ancient.

In 1939 members of the Colorado Mountain Club went 12 miles southwest of Walsenburg to observe portions of a mammoth.

Those paleontologists from New York periodically returned to continue their search for prehistoric life. In the early 1950s they spent three straight seasons here, and they returned in 1957 for even more specimens. They were concentrated in the same area around Farisita.

Distinguished departed denizens

The highlight was probably in 1953 when they were accompanied by film crews to make a CBS special television show on paleontology. At that time, one declared they were working in a bed that was a “veritable goldmine of rare fossils” from the Eocene, including another eohippus. This was the most national publicity Huerfano County had ever had until the 1980s when Marlboro commercials were filmed around Goemmer’s Butte.

One of their best finds was a ninety million year old mosasaur. Not only were they exploring and digging, they were preparing the finds for the long trip home to the museum, which is why you can find Huerfano represented in the New York Museum of Natural History.

The mosasaur was a marine lizard related to the monitor lizards of today. It lived in the sea, but breathed air. It lived in the Cretaceous Period. Another was found on Claudia Capps’ ranch in the eastern portion of the county by oil drillers. Hers was a 50-foot long model, and it was just one of several found in that locality.

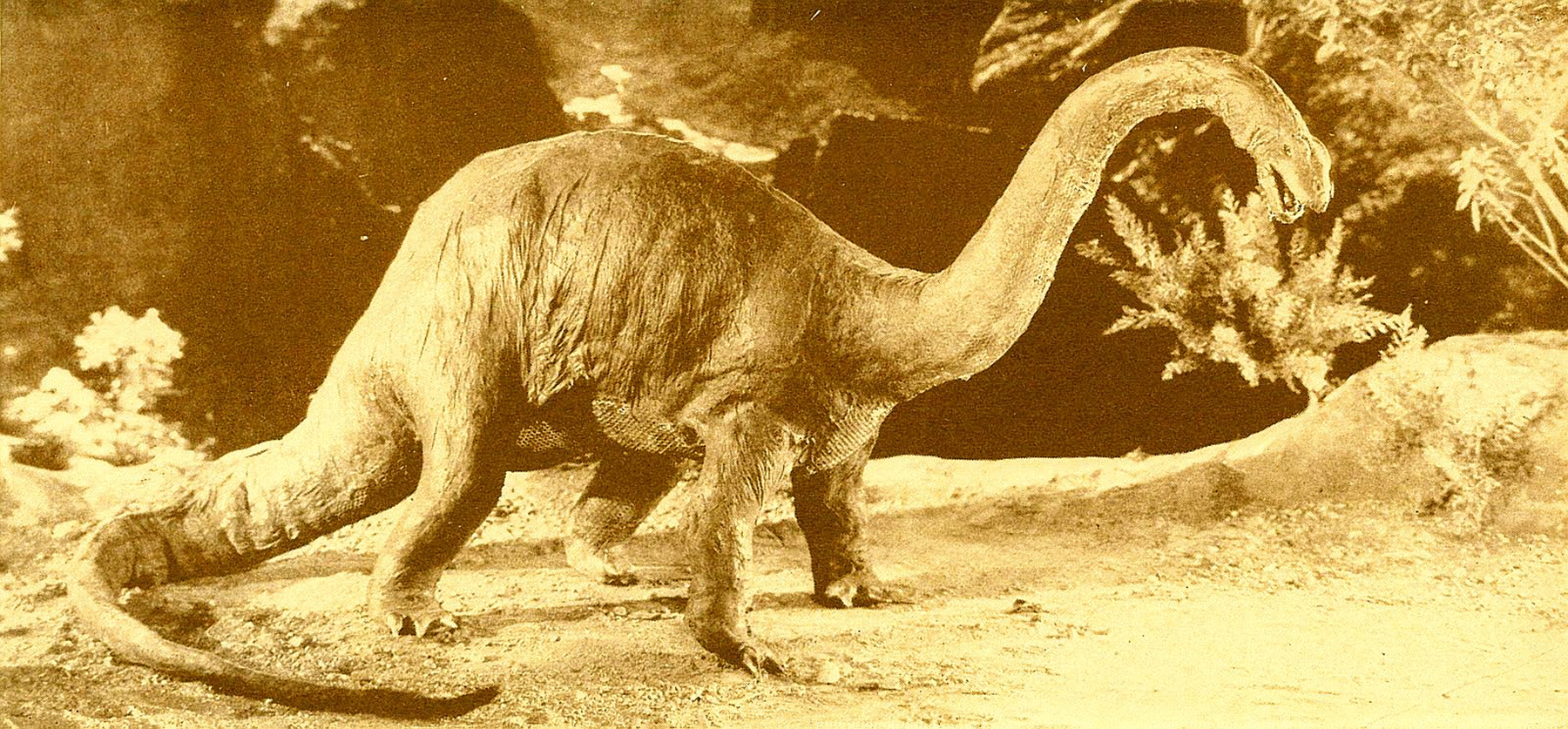

Of course, the most important find for paleontologists was the trackway in the Purgatory canon. It wasn’t until the 1980s this was identified, and it is known as the longest trackway, or continuous trail of footprints, on the North American continent. It contains some 1,300 separate impressions stretching a distance of a quarter mile and dates to 70 to 66 million years ago in the Cretaceous. They were called Brontosaurus tracks until scientists changed the name to Apatosaurus, which are sauropods, or “veggiesaurs” for the fans of the movie Jurassic Park.

Now if we were talking geology here, we could tell about specimens from Las Animas County around the famous K-T boundary that are now in the Smithsonian Institute, or all the colleges that sent their student field trippers to the Scenic Highway of Legends to inspect the singular rock formations, but we’re not.