by Pat Veltri

COAL CAMP COUNTRY — Woodul’s best memories of Koehler centered around her school experiences. She loved school! Early on, before formally starting school, she decided that she wanted to be a teacher. Perhaps she took a cue from her maternal grandmother who had been a teacher in Italy. Woodul pursued her lifelong dream and became an educator, racking up some impressive teaching awards along the way, and later earning the credentials for an administrative position. Woodul’s lifelong love of learning actually started a year earlier than it was supposed to. She says, “Because January first was the cutoff for starting school, and my birthday was twelve days later, my mom persuaded the principal to let me start school a year early. Quickly I was promoted a grade. When I out-spelled all of the third graders, the teachers wanted to promote me another grade. My mom said, ‘No’. The ironic thing is that I consider myself an average speller and have become very sloppy in my proofreading, especially when working on my phone.”

School days

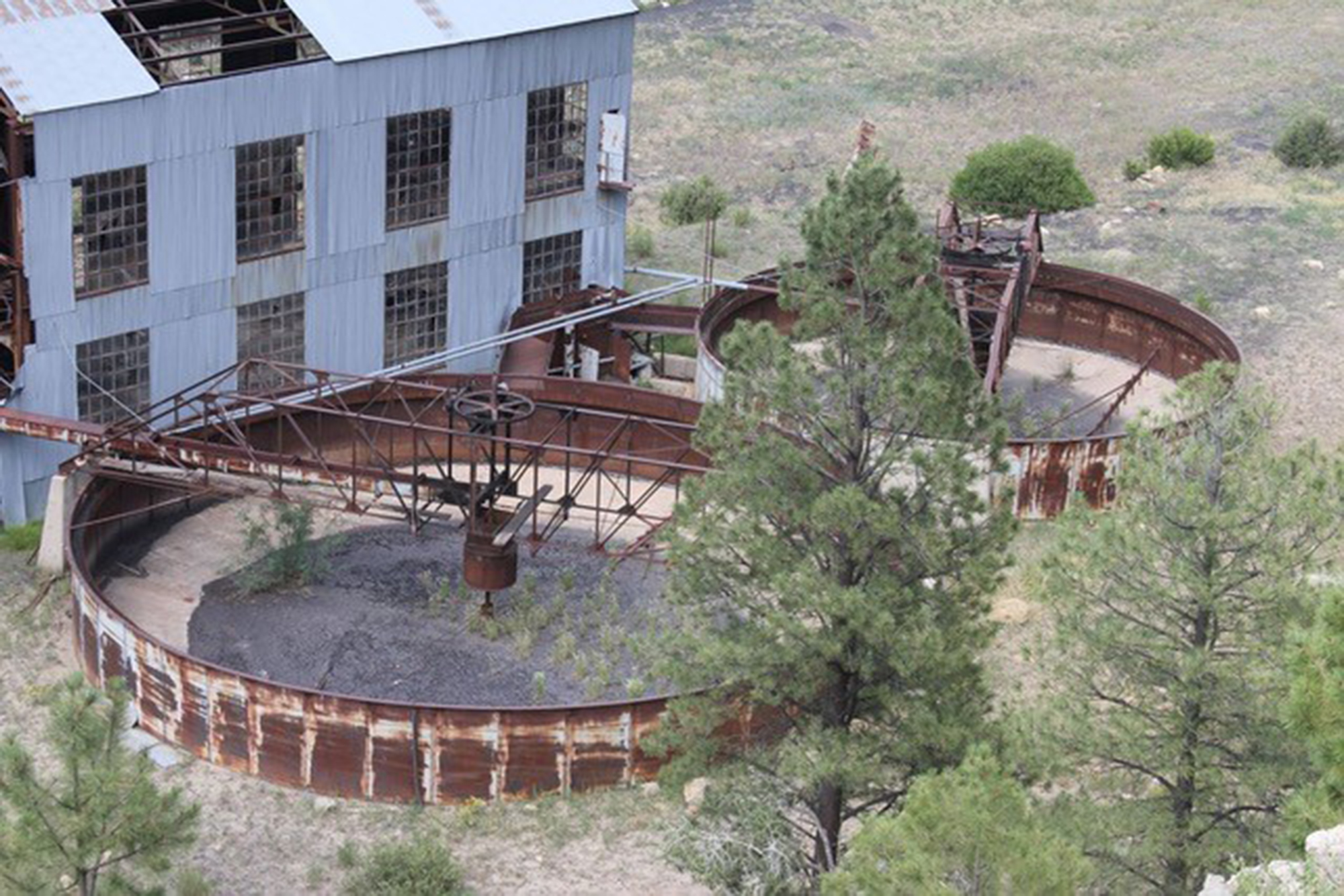

The original two-story school house in Koehler burned to the ground in 1923 and was never replaced. Instead, several 24 x 24 cinder block homes were converted into classrooms. Each grade had its own building and teacher. Woodul says she remembers there were “about four students in each class that were ‘Anglo’”. Most students had another first language. Hispanic students were not allowed to speak Spanish in the classroom or on the playground. This rule was strictly enforced. It bothered Woodul when she “heard students being chastised for speaking Spanish.” Years later, at a high school reunion, she experienced a pivotal moment – she learned from one of her childhood friends that Hispanic parents asked for their children to be immersed in the English language. “As a former secondary teacher and administrator, I do not believe in English as a second language,” she states. She goes on to say, “I saw firsthand how well all of the students learned in those small mining camps. I have been able to see how successful those students became later in life. Full immersion worked really well. Having very tough teachers helped too. I especially remember my fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Rathbone. If anyone missed a question, she threw anything that was on her desk at the student. Books and erasers were what I remember most. I never had that happen; I was extremely motivated! I did have her as piano teacher for two years. If I missed a note, she hit my knuckles with a ruler. Believe me I practiced!”

Woodul became a first time job-holder when she entered the third grade. She was hired to pick up the mail for one of her favorite camp ladies – Jennie Baker – and collected a “salary” of fifty cents a week! “I was RICH!” she exclaims. “Most of my money went into my savings account in the bank in Raton, but often I would buy two peanut butter cups. They were two for a penny. The camp stores were owned by the mining company. At first miners were paid in script so they would have to pay higher prices. Later they were paid in cash.”

Strike!

While still a schoolgirl,Woodul began to understand the distinction between labor and management. All four of her Italian grandparents left Colorado during the Ludlow Massacre, an attack on striking coal miners and their families by the Colorado National Guard and Colorado Fuel and Iron Company guards. The massacre, which occurred on April 20, 1914 at Ludlow Colorado, resulted in the deaths of 25 people, including eleven children. “When women and children were killed in a strike situation, my grandparents left Colorado,” she says. She states further, “On April 23, my paternal grandmother spent the night under a bridge in cold Colorado weather with her newborn son – my father. My maternal grand parents rode a train to Maxwell with a year-old son. My grandmother was pregnant with my mother who was born on July 23, 1914, three months after the April uprising.”

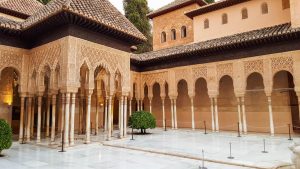

Much has been written and said about the eclectic array of cultures meshed together in coal mining camps. According to Woodul, “the owners of the mines made sure to have many cultures because they did not want the miners to be able to communicate with each other and work together to change mining conditions.” Referring to Ludlow she says, “Miners had rebelled about working conditions. It wasn’t really about pay, but about working conditions.” During Woodul’s time at Koehler, the dominant nationalities were Hispanics and Italians, despite the efforts of mine owners to recruit a mix of ethnic groups.

Woodul’s grandparents left Colorado during the strikes, but her father later became part of management, being a supervisor of mining activities at Koehler. “My parents were registered Republicans. The minute my father knew there would be a strike, he came home, we packed and went to Denver to visit his sister. When the strike was over we came home,” she states.

Dangerous times

Lurking in the background hidden deep within the daily hum of camp life was the anticipation of danger, an underlying anxiousness and unease that was brought to the surface by the shrill wailing of a siren – signaling trouble in the mine. Cave-in, explosion, fire, runaway coal car? As the piercing noise echoed into homes, schools, the company store and post office, those listening were gripped by a cold fear accompanied by troubled thoughts about who might be injured or dead. Is it my son, my husband, my father, my uncle, my grandfather? Woodul was in high school when the sirens were for her father, “My father had a coal mining car run over him,” she states. “It injured his hand and ran over his legs. As difficult as this is to imagine, he spent nearly a year in the hospital in traction.” Following a lengthy recovery, he was back on the job.

Some years later Woodul’s father was once again a victim of misfortune. While inspecting a part of the mine for potential safety issues, the roof gave way and he suffered an injury that was ultimately fatal. “I was a sophomore in college when a mine caved in and he survived for two days and passed away,” she sadly recalls. She continues, “My older brother Johnny was out of college; I was in college, my brother Kenny was a junior in high school, my sister Doris was eight and my little brother Bobby was four. A lot of that was a blur. I remember details, though, such as all of my former teachers were at his funeral and that meant so much to me. By that time we had moved to the Superintendent’s house in the camp. It was the nicest house. Because my brother was a junior, the decision was made to allow my mother to stay in camp housing until he graduated a year and a half later. Usually widows had one year to move and sometimes had to leave as soon as possible. My mother moved to a farm in Maxwell that my parents had purchased years earlier.”

Memories stay with you

Living and growing up in Koehler, Woodul was inspired by the example of a couple of adults in the coal town. “I have several heroes from that time,” she says, “first, Pete Maga. Pete was a co-worker of my father’s. Pete traveled on a boat from Italy at the age of nine. I cannot even imagine that.” She continues, “Another was Pauline Yaksich. When she was pregnant with her fifth child, her husband was killed in the mine. The company took care of her, which was rare. They gave her a house in Koehler, and she cleaned the schools. Recently her youngest and only surviving son (Judo) reminded me she arose at 4:30 am every morning to light the stoves for the schools and then of course cleaned each of the classrooms after school.”

Woodul honors and appreciates the memories of her life as a coal camp kid. Parents, teachers, and other coal town role models helped form her character and set the scene for her successful career path. “Personally I would not trade for my youth in Koehler,” she says. “I was happy, healthy, and learned to get along with everyone. The schools were good. Kids respected their elders and were good kids.”

Nowadays, Woodul lives on Barlett Mesa with her husband Jack, a retired airline pilot, and an ever changing menagerie of animals.